The Power of the Second Curve

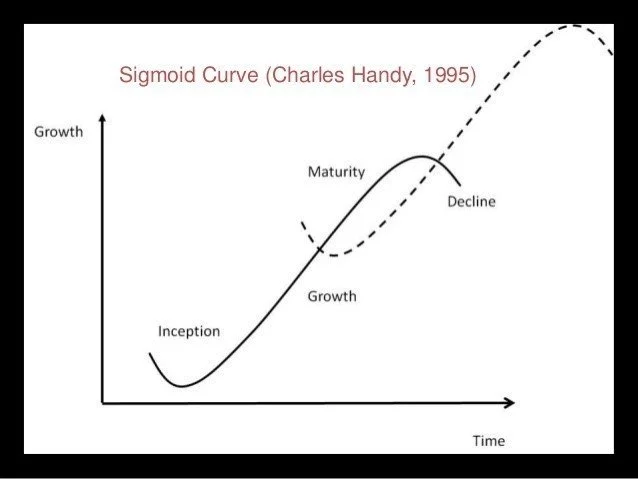

One of the most important lessons I’ve learned in leadership, consulting, and life is the concept of the second curve. This concept created by Charles Handy some 30 years ago frames growth in segments over time. It’s a simple but powerful idea: what got you to success on the first curve will not necessarily carry you to the next level. Growth requires us to step away from what we know, what we do well, and what feels safe—to retreat a bit and embrace something new, often uncomfortable, in order to reach new heights.

Most of us naturally cling to the first curve. It represents accomplishment, mastery, and a sense of confidence. But the danger of staying there too long is stagnation. The second curve begins when we choose to take a risk, to leave behind the comfort of certainty, and to step into a future that is undefined.

The second curve demands discomfort. When things are going well, it’s tempting to relax, to settle into what works. But growth rarely happens in that space. The willingness to look for discomfort—even when success is present—is the discipline that creates momentum for new possibilities. It’s not about recklessness; it’s about intentionally seeking the edge where you are stretched, tested, and forced to learn again.

Think about a nonprofit leader who has mastered donor cultivation in one model of fundraising. If that leader stays on the first curve, the work will eventually plateau. But if they are willing to experiment with digital engagement, AI-driven donor analytics, or new collaborative giving circles, they step into the second curve. The initial steps may feel awkward, even like regression, but the long-term gains are transformational.

Not everything requires reinvention. Some elements of life are so foundational they remain on the first curve—stable, consistent, and sustaining. For me, this includes the love of my wife, the value of family, and my personal faith. These aren’t things to disrupt or “jump away” from; they provide the grounding and security that make the leap to the second curve possible.

It’s precisely because these anchors exist that I can risk discomfort in other areas. The first curve gives stability; the second curve offers growth. Both are necessary.

The hardest part of the second curve is the leap. It’s moving from the known to the unknown, from the confidence of success to the humility of starting fresh. This leap is not about abandoning what has worked, but about recognizing its limits. At some point, excellence requires change.

In business, this might look like innovating products before the market demands it. In personal growth, it might mean pursuing a new skill or interest even when you’ve already achieved mastery elsewhere. In philanthropy, it might mean reimagining how donors experience connection and purpose rather than relying on established models.

The second curve is not a rejection of the first, but an evolution beyond it. Growth, excellence, and innovation happen when we dare to embrace the unknown. The real challenge is not in reaching the first curve—it’s in having the courage to leave it behind.